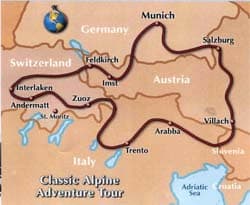

Beach's Classic Alpine Tour

It had been a long day over many glorious miles. Late in the afternoon half a dozen of us, admittedly a bit weary, were standing high on a mountainside overlooking a beautiful Alpine valley... with no sign of our destination. One of our number said, "Gee, I'd really like to be at the hotel about now, having a nice cold beer."

Our fearless leader, Rob Beach, looked at him, smiled and said, "In a few days you'll be home, and you’ll think back to this moment and wish you had spent more time riding your motorcycle." Truer words were rarely spoken. We got back on our motorcycles and continued on.

People sign up for organized motorcycle tours for a variety of reasons. The primary ones are that after a long flight it is pleasant to be met at the airport, taken to a nice hotel, given a motorcycle to ride and not have to schlep your own bags around. But the main purpose of such a tour is usually to ride new roads, to take a motorcycle to places you've never been before. After all, this is why most of us ride. Although different tour organizers have different feelings about how exciting those roads should be.

Myself, I like mountains, because I find those twisty, curvy roads are a lot more fun than crossing the Great Plains. And Beach’s Classic Alpine tour gives you mountains, and more mountains, then a few more mountains on top of that. It is sport-touring at its very best.

Let me tell you that Rob Beach knows his Alpine Roads, and knows them well. I’ve been motorcycling in and around the Alps since 1957, and what impressed me most was Rob’s familiarity with the terrain. We would be whipping down some little two-laner, Rob’s turn signal goes on, and we slip down between a barn and a house and find ourselves on one of those single-lane paved byways that are to be found all through the Alps, crossing a field, through a woods, angling across a steep meadow and climbing to a little-used saddle high in the hinterlands. Usually with a Gasthaus offering coffee and croissants.

The Beach tour is a rider’s tour. It has good hotels and hearty food, but these are secondary to the great roads and riding. Other tours might offer more luxurious lodging and seven-course meals, whereas Sue and I were quite happy with the accommodations and the three-course dinners… as were all of the other riders. After all, we had come to ride, not only to sleep and eat.

Don’t get me wrong, the hotels were wonderful. Like the charming (a very appropriate word in this instance) Alpenrose in the heart of Feldkirch in Austria, which has been hosting guests for several hundred years. I especially liked the modern Mercure Hotel on a mountainside several thousand feet above Interlaken, Switzerland, with a spectacular view of three great Alpine peaks to the south. Or the Hotel Evaldo in the tiny town of Arabba, Italy, where over a hundred motorcyclists were staying. There was no rally or race, just a hundred riders who wanted to ride the local mountain passes, and the Evaldo is known for its friendliness to motorcycle aficionados.

The number of motorcyclists on the Alpine roads is impressive, something we are not used to here in the United States. If there is a major gathering, like Americade or the Laguna Seca MotoGP, thousands of motorcycles appear, but in the Alps these riders are just out for a ride. We spent a weekend around Andermatt in Switzerland, and passed hundreds and hundreds of motorcycles as we crossed over the Furka, Nufenen and St. Gottard passes.

Dadi & Chiavarde

(Nuts & Bolts)

The Beach motorcycle touring company has been doing this Classic Alpine trip since 1972, and Rob Beach leads all the tours; he knows his way around. It runs a two week schedule, arriving in and departing from Munich on a Sunday, with all hotel rooms included in the price. Which in2006 was $5,280 for the rider, $3,510 for a passenger. In 2007 the price will include the use of a BMW F650, F800, R1150R, or R1200GS, though upgrades to the rest of the BMW range are available. For $450 extra you can get a K1200R, for $750 the masochistic can claim an HP2.

The trip covers a minimum of 1,900 miles, a maximum of however many times you want to go over the Furka Pass. You buy gas, lunches and a couple of dinners on the free days. Gas runs a little over $4 a gallon, lunches can be a picnic on a mountainside or an elaborate meal. An ATM card is the easiest way to get cash; Germany, Austria and Italy use Euros, while the independent Swiss hold on to their franc… though Euros are quite acceptable. As are major credit cards.

Alpine weather can be warm or cool, dry or wet, so Sue and I wore Olympia riding suits, which have a protective mesh outer layer and a warm and waterproof liner. I think we donned the liners twice, as Europe was enjoying a hot “Sicilian Summer” and most days in the mountains were in the 80s (Fahrenheit), roughly 30 degrees Centigrade.

All the particulars on the trip can be had by running up Beach’s Motorcycle Adventures at www.bmca.com on your computer, or dialing (716) 773-4960. Once you have signed up for the tour, you will receive a steady stream of worthwhile information, and the day before your departure Rob will call just to make sure everything is OK. That’s a very reassuring touch.

This trip began with a long flight from California to Munich, Germany where Rob’s sidekick, Al Walker, met us at the airport. Kiwi Al works the Beach tours in the New Zealand Alps, and comes to the European Alps in the northern hemisphere’s summer. Tour headquarters are in Olching, on the outskirts of the big city, in a pleasant hotel backing on the Amper River. Germany happened to be in the middle of the frenetic world soccer championships, and anyone wanting to see the heart of Munich could take a short train-ride in rather than fight traffic on a motorcycle.

Nineteen North American riders had signed up for the tour, their ages ranging from 16 (traveling as pillion) to the retired. Rob uses BMWs, mostly the R1200GS models, although one couple had asked for an extremely trick Bavarian-made Renaissance sidecar hooked up to a Triumph Rocket III. Three of the riders were women, and five of the bikes as well as the sidecar outfit were two-up.

Rob has put together a book for his Alpine clients, and a well-done volume it is. Each day there’s two or three possible routes listed, or one can follow Rob. Everyone has been sent a set of 1:300,000 maps of Bavaria, Austria, Switzerland and NE Italy, on which the roads are easily found and followed. GPS units have been dialed in as well. With this navigation tool a rider can go off on his own and follow all the lovely circuitous little roads that Rob has found, doing the speed he wants, stopping when he wants. If you already know the way you want to go, you can leave the maps in the tankbag and follow the little arrow. In my mind this is a great asset in the world of organized motorcycle tours, giving much more freedom to the clients.

Beach tours emphasize that this is not a straight-road tour; the whole purpose of the Alpine experience is that you get to ride squiggly roads which go endlessly up and down. If a rider is not comfortable negotiating hundreds of hairpins, he or she should not sign up for the trip, a point Rob emphasized in the brochures. The east side of the 9,035-foot Stelvio Pass, in Italy, has 48 hairpins alone.

Follow Rob can be quite entertaining, because he claims to have no pre-planned route and takes off in any direction he feels like. Late one afternoon we came upon a police blockade and were told that a landslide had just closed the road ahead, meaning we would have to go back and take another route to the hotel. “We’ll be late for dinner,” moaned one of the riders.

“No we won’t,” said Rob; “dinner never starts until I get there.”

Depending on the chosen routes, in two weeks we would cover upwards of 2,000 miles, and go over 30 or 40 passes. Of course the more diligent could easily up the miles and number of passes. The Alps actually form a towering arc of some 700 miles, curving from southern France through Switzerland, western Austria, a bit of Germany, northeastern Italy, Slovenia, all the way to the Dalmatian coast. Over 400 passes are listed, from well-paved highways to footpaths. We were in what is roughly referred to as the Central Alps, which do have many of the best roads. The Swiss Nufenen Pass may not sound very high at 8,052 feet, until you remember that sea level in the Mediterranean is less than 150 miles away. Our lowest pass was Passo San Giovanni at 940 feet, on the north end of Lake Garda.

Much of the best riding is done on little “farm” roads, for lack of a better word. Hundreds of miles of single-lane asphalt has been laid through those mountains providing safe passage for tractors and farm equipment. The locals simply realized, after motorization came following World War II, that this is a better way to preserve the land than gouging up dirt.

They’re perfect for motorcycles, and are really where the Beach tour excels. These Alpine lands have been farmed and timbered for a thousand years, and to the American eye-accustomed to endless Iowa cornfields and clear-cut forests-the way everything has been maintained is a marvel. Stacks of cut wood are seen in the forests, harvested every year, and the forests are still standing. The farmers are considered the caretakers of the mountains, and they do a very good job.

One of our most entertaining passes was in the Triglav National Park of Slovenia, one of the new countries created from old Yugoslavia that borders on Italy and Austria. Rob had highly recommended this little detour, and Sue and I were riding alone. We crossed from Italy to Slovenia over a low pass, the Predil, and the road dropped into a long valley, then turned and started running up alongside a river. With a mountain seeming to bar our way. At the bottom of the mountain we approached a hairpin curve, and a sign bore the number 49. This was rugged country, through thick forest, and the wood-shaded hairpins just kept on coming. At the top of the Vrsic Pass at 5,284 feet was the requisite little restaurant, and then we began our descent. Forty-nine hairpins later we were on the other side of the mountain.

When we got back to Olching at the end of the tour, there was satisfaction on all our faces. And yes, when we got home we would have regretted any day we chose to short-cut to the hotel rather than ride those two extra passes.