Romance, Adventure, Weddings and Things Unseen on Beach's British Tour

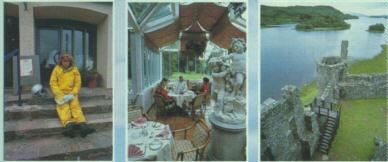

Collage of scenes from Britian

Without hesitation, I can say it was the worst weather I'd ever ridden in. It was like being hit in the face with a soggy mop. Sheets of rain driven by gale-force winds had us huddled into the wet-nylon smell of our rainsuits on England's A1 Motorway. Five of us pulled into a petrol station near Doncaster to fill up our BMWs. A guy in a car yelled over, "Having fun, mates?"

"Sure, we're having fun!" Rob Beach shouted back. "We're having a party!" Suddenly, we were arm in arm, hoofing left, right, left like a chorus line of drunken yellow ducks. Riding in heavy British weather can drive you crazy, can make you go bats-British bats.

It was August 1986, and we were in England as participants in the first Beach's British Bat, a 21-day organized motorcycle tour of England, Scotland and Wales. You've probably heard of the Beaches; Bob and Liz have been running their Alpine Adventure motorcycle tours since 1972. The British Bat is the brainchild of their son Rob.

The Beaches initiated a touring concept that really works yet is relatively unknown outside of motorcycling. They book hotels, provide an itinerary with maps, arrange for bikes and a luggage van and then personally accompany the tours. The advantages include easy access to new BMW motorcycles, the freedom to rise when you like and ride whatever pace and route you prefer and a group of like-minded souls to share it all. You always know where your next bed is, and the only rule is that you be in by 7:30 p.m. or call, so Beach doesn't worry.

Upon arrival in London, tour members were transported to the friendly confines of the Noke Hotel in St. Albans. The Noke is like a country home, with nooks and crannies, a fireplace in the pub and hair dryers and pants pressers in the rooms. The waiters can be found playing cricket on the back lawn in the afternoon. Show enough interest, and you just may be invited to pick up a flat-sided bat and have a whack.

The majority of the hotels on the British Bat were charming, clean, delightful places. Having spent five weeks touring Europe with my wife Margery on our own in 1984, I can verify that lone travelers rolling into a foreign city at night are not often likely to luck into hotels of such charm and quality.

The day following our arrival, Rob drove the riders to London to collect their rental or European-delivery BMWs. On the way, he explained the intricacies of zebra crossings (striped zones surmounted by a blinking yellow light in which drivers must stop for pedestrians), roundabouts and left-hand riding.

That left-hand business bothered me before the tour. I wondered if in an emergency my instincts would take over, say, "Let me handle this, big guy," and gallantly slam me into the grille of an oncoming Iveco truck. It didn't happen. Riding left and looking right requires concentration, but after four days, I felt at home on the roads. Still, turn me loose in a parking lot and bingo-I'd snap to the right quicker than Jerry Falwell.

Stonehenge is now fenced off from

the public to preserve its mysteries.

On our second day, we crossed paths with Winchester Cathedral, which was the subject of a hit tune in 1966. It's dark and in need of cleaning, which is understandable as it was consecrated in 1093. An old priest befriended us and said, "I so admire your Benjamin Franklin." Adding in a low, confidential voice, "But he was quite a lecher." He showed us where, in the floor, were buried two relatives of George Washington-a man the priest also admired.

The British fascination with cathedrals and monuments reaches back thousands of years. At the Avebury Stone Circle, about 50 miles north of Stonehenge, a fellow handed me two sticks and instructed, "Point them at the stone, and walk forward till you feel the force." Force? The only forces I believed in were horsepower, head-ons and speeding tickets. What did he take me for?

Grasping the fiberglass divining rod, I approached the ancient stone circle, and darned if the end of the thing didn't start to pull downward like the persistent nibbling of a fish on a line. Soon the pull became forceful. "See," he said, "it gets stronger when you stop disbelieving." Now the slender rods bent as if a fighting bluegill were on the other end.

The British Isles are sprinkled with these sarsen stones. Some are smooth and bridged like Stonehenge, some remain natural but are arranged in halfmile circles with 20-foot ditches around them as in Avebury, and some are just lone rocks set on end in a pasture. No one can explain with any certainty how these many-ton rocks were moved or who put them there or what these mysterious force lines are that surround these ancient monuments. I found it best just to accept the feelings of these places and not try to explain them.

The author couldn't explain it, but

he could feel it. This is the Britisher

who beckoned him to sample

the mysterious forces at Avebury

using a fiberglass divining rod.

After a few days, the tour routine became established. Have your bags down by 8:00 to be loaded into the van. Leave when you wish, and ride with whom you choose on whatever route you desire. Dinner would be at 7:30, except for one night of each double overnight when we were on our own. As dinner wound down, Rob would ask how the day had gone, what we had seen, who had run afoul of the laws of traffic or gravity. To those who'd had tough luck, he'd award one of his "Aw Caich" buttons. Rob defined this word as Gaelic for what you say when you accidentally flatten your thumb with a hammer. Then he'd preview the next day's ride and suggest some alternate routes and sights to see.

A word about the food in Britain. How often have you seen a British restaurant in the U.S.? You don't see British restaurants because they eat pretty much what we do-steaks and pork, a bit more veal and lamb. Yet most Americans do not feel entirely at home with British cuisine.

All breakfasts were included with the tour, and some hotels put on quite a spread-fruits, breads and a selection of cereals. Poached eggs are always available for breakfast as are the optional kippers or smoked herring. Forget salads. The British idea of a salad is a poached egg on one lettuce leaf with mayonnaise. Water is not automatically served with meals, and you must ask for coffee with dessert. Your sweet tooth will love the layered, fall-down-and-eat-your-way-to-the-bottom treats on the sweet trolley.

With few exceptions, the food on the Bat was good to excellent. I salivate at the memory of the lobster thermidor at the Bontddu Hall Hotel in Wales. Most of us agreed the best food of the trip was at Harvey's, that little place in Lincoln we stopped at the day we survived the wettest ride of our lives.

In Wales, we found the town names difficult to pronounce as letters have different sounds in Welsh. Bontddu, where we stayed the fourth night, is pronounced "Bont-thee." Our group thus Americanized Welsh names for understandability. Now Dolgellau became Dogtown and Betws-y-Coed was an easy conversion to Betty Coed. We likewise simplified Porthmadog to my favorite, Port (and polish) my Dog.

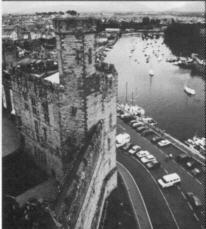

The author's favorite castle was

Caernarfon in Wales, where you

climb stairs indented by 800 years

of castle guards and peer over the

walls for 13th-century pirates or

roving bands of killed renegade Scots

coming from the landward side.

A wealth of castles graced the route. Windsor Castle is near London. Stalker Castle is a trim, downsized fortress set on a tiny island near Fort William, Scotland. The trilaterals, Skenfrith, Grosmont and Llavetherine, form an exact equilateral triangle precisely five miles on a side. Buckingham Palace was just down the street from our final hotel, the Royal Westminster, in London.

One of my favorite experiences was the medieval banquet at Ruthin Castle. Among a crowd of perhaps 100, we sat in a large hall at long, rough tables, with bibs around our necks and only a knife to do battle with dinner. Madrigal singers performed, and the master of ceremonies, decked out in period dress, told jokes that were already old in the Middle Ages. We slurped leek soup from bowls, slopped at broad beans with our fingers and carved up lamb haunches with our blades. Maids fortified us with a ready supply of mead and spiced red wine as we took part in the limerick contest and wiped our hands on our dripping bibs.

That first Saturday, the left-hand driving came out to bite one of our number. Ron Andrews traipsed into the hotel in Buxton with a network of stitches in his lower lip. He'd been riding along on his rented R80RT, when a VW van drove down the wrong side of the road. "I moved all the way over to the left," Andrews told us, "but there wasn't quite enough room. He clipped me, and I went flying into a hedge." He was awarded an "Aw Caich" button at dinner.

The Bottom Line on Brit Touring

0ur typical impression of tours is of a bus load of blueheaded old ladies being herded from cathedral to restaurant to hotel. Be advised the Beach tours are not one of these hand-holding experiences for the spineless. Beach tour participants are expected to be competent, experienced motorcyclists able to adventure independently.

This first Bat was a shakedown run with a small group of Beach tour veterans. The Alpine tours usually consist of 30 to 40 people, the number limited by the size of the luggage van and number of hotel rooms. Our group was only 14 strong, including Beach and the van driver, but future Bats will be larger. Beach researched his hotel selection well, and many of them were great little places, although a few were threadbare and a little overused. Beach won't include these on future tours.

The 1987 British Bat, scheduled for August 9-30, will be at least $2800 per person for the double-occupancy rate. Motorcycle rental and fuel costs are additional. In 1986, rental costs for the three week tour, including insurance, were $900 for a BMW R80, $1000 for the R80RT and $1100 for the new K75C triple. The weak dollar, however, is bound to cause a price increase. In addition, Beach can also arrange overseas delivery if you wish to purchase a new BMW there and bring it home.

Just four days after his split lip, Ron was out exploring the Isle of Skye on his own when he went down again. The gash on his chin, sore shoulder and abrasions were painful, but it was the broken wrist that prevented him from re-mounting his thrashed RT. Had he been on his own, Ron would have had to find a way to get his bike and himself home. The incident would have ruined his dream vacation. On the tour, however, his damaged bike was put on the next train to London, and Ron was able to complete the trip in the luggage van.

Taking your own bike for the tour is hardly worth it. Round-trip air shipping is about $600. You may have to ride hundreds of miles and fly out on a specific day of the week to take advantage of any deal, further eroding your savings. Then you have to buy insurance. The wear and tear of about 2500 miles will now be on your bike, and if something bad happens, all expenses will be yours. These factors offset any financial advantage of shipping your own machine.

The Bat provides several double overnights to allow members to catch up on their laundry and sleep or to wander the local countryside. Guided by a map drawn by the lady at the counter, Margery and I hiked into the hills above the Sun Hotel in Coniston. The trail led through trees, across a crude bridge to the remains of an old mine.

Far above us along the ridge, a scattering flock of sheep wended its way down the hill. The frustrated shepherd's voice carried below to them. "Hey, hey, up lads-come on!" His black and white dog ranged about, leaping from rock to rock, working the sheep, turning them. Finally, the flock swept by us. As the shepherd strode past, his pipe leaving a fragrant wake of smoke, he winked and said, "Rough life, eh?"

Scotland sits atop England's shoulders, a rugged, sparse land of hills, lakes and fields. The Roman Emperor Hadrian designed his wall in AD 122 to guard against the wily Scots.

Smack in the way between our overnight in Ayr, Scotland, and Oban to the north lay industrial Glasglow. Beach's guidebook suggested the alternative of taking the ferry to the Island of Arran. After paying �12.40 ($18.60) for the ferry ride, we met a young Italian. Luigi was from Rome, touring on his 1975 Moto Guzzi. Neatly bearded and articulate, he told us he planned to come to the U.S. in a few years. We gave him our address. Following our tour, we would travel another week on the Continent, staying with two families in Germany and one in the Netherlands. In each case, we had met them just as we met Luigi. In each case, they had stayed with us in California, and now we were returning the visits. International travel is a fine way to meet people in, and from, other countries.

Ferry to the Isle of Arran

Arran is a jewel! After the 55-minute ferry ride, we reached the green island and promptly headed inland toward Blackwater Foot. This coastal town reminded me of Nova Scotia (New Scotland), and we stopped for tea.

Britain has tea rooms whereas we have coffee shops. They smell like bakeries and serve steaming pots of fragrant tea that the Brits enjoy with cream. Tea rooms are generally cozy, with a ready supply of scones and little cakes, breads and jellies and jams. We welcomed these chances to get warm and meet the British at their leisure.

Riding along the sun-drenched coast, we saw, protruding from the ground like a 15-foot knife blade, another sarsen stone in a field of sheep. Behind it a craft shop sold sweaters from local weavers. Everywhere in Scotland you can find good, thick sweaters. In the late cool of a summer's day and with prices ranging from $10 to $30, it's easy to understand why they're so popular.

We had to scoot to make the Lochranza ferry, blitzing the two-laner that winds along a sheltered cove. We got airborne on some dips and passed Luigi's Guzzi as he slept in the grass. We reached the ferry as it was unloading. It held only seven cars, but at least 20 were waiting. We pulled to the side, tried to look small and were waved aboard.

Those final 40 miles to Oban, Scotland, are some of the finest asphalt in captivity. The road is a well-marked, smooth black ribbon meandering along a large inlet with sheep-covered hills, neatly trimmed fields and the occasional sarsen stones standing like sentinels.

The Hotel Alexandra in Oban fronts on the Firth of Lorn; from our window we could watch the ferry New Caledonian muscling its way to and from the Island of Mull. During our two-day stay, we rode the 20 miles to Loch Awe to visit Kilchurn Castle. Walking out through swampy lands, we were set upon by clouds of midges, gnats with teeth like piranha that are to Scotland what mosquitoes are to the Midwest.

From here we took the road less traveled (A87) up, then down, a long, rocky valley to a wonderful view of Eilean Donan castle, dreamlike and delicate in the distance. North on A890 and A832, the 64 miles to Inverness were all onelane roads, plenty wide for a bike to meet a car.

Beach scheduled the tour to correspond with the Edinburgh (pronounced "Edinborough") Tattoo, named for the drum tattoo that in the past called soldiers to the barracks from town. That evening, massed bands of drummers, buglers and pipers shook the stands when they passed below.

Edinburgh was our favorite city on the tour, a free-spirited place that's like a more quiescent London, a less decadent Berlin or a less sophisticated Amsterdam. Monuments are sprinkled all about the town. A huge park parallels the main street, and the long castle is silhouetted on the craggy rocks above. Pub conversation is lively; you can get a good pint of bitters or ale and watch the punkers stroll by.

One highlight of our tour was a moment that Beach cannot guarantee on future Bats. A couple on our tour was married near Edinburgh on the canal boat Pride of the Union, which specializes in weddings, dinner cruises and dancing. As we were toasting Weldon and Sandy on the landing before the ceremony, a bagpiper happened in and, upon request, played "Amazing Grace" and some Scottish tunes for the bride.

The ceremony was held in the cool, paneled darkness of the Pride, the canal waters dappling her ceiling as she creaked and sighed at her mooring. Dinner was an enjoyable selection as we glided along to the strains of organ music played by a round-faced, good-humored musician wearing a tux. The wine flowed as he pointed out the history of the numbered bridges along the canal.

As the sun set, we disembarked and walked along the aqueduct, toasting the gentleman whose palatial manor house reclined below. Back on the boat, they were stowing tables, and the serious dancing was about to begin. The staid organist suddenly turned to soft rock with appropriate automatic rhythms. He played the chicken dance, and even the minister got up to wiggle his tail feathers. Then to a cha-cha beat, we formed a conga line and swayed in a serpentine down and about the boat in a laughing, sinuous line. We all vowed that when we returned for the next British Bat, we'd bring another couple to marry.

Britain is reputed to be wet and foggy, though summer is the driest time of year. It was cool enough for leather jackets and pants every day. Our rainsuits were on only twice in the first two weeks. But, oh, that third week.

Hurricane Charley had bounced off the eastern coast of the United States, churned itself into a fury across the Atlantic and now fell upon the British Isles like a wolf on a pork chop. Unfortunately, this also happened to be our day to ride from Newcastle-upon-Tyne to Lincoln.

Driven by gale-force winds, the rain battered us in heavy, pounding sheets. We stuck to the motorway, bundled into our Rukkas and Dry Riders, and hung on. The television that night called this the worst August storm in 45 years, and the wettest 24 hours in Britain since they'd started keeping records.

Lincoln was worth the ride. Our D'Isney Place Hotel was a converted home with comfortable rooms (most with armoires and fireplaces), a country manor house atmosphere and breakfast in bed. The well-preserved Lincoln Cathedral, with its famous imp, enthralled us for hours. That imp is the figure of a mischievous gremlin that, the legend goes, was turned to stone by God for disrupting services at the cathedral.

Great Yarmouth, our last overnight before returning to London, is Britain's answer to Las Vegas. The oceanfront drive is a hotel row with tacky video arcades cheek by jowl with fast-food shops (hey, jellied eel!), slot-machine parlors and garish neon places named Circus Circus, the Sands and Aladdin.

"Whatever you do, don't order tea," Weldon and Sandy warned us at the Royal Westminster Hotel back in London. Why? This was the ritziest hotel I'd ever been in. "Oh, it's good all right, served on fine china, and you get little cookies with it," Weldon told us. "But tea for two here costs �6.75 apiece; that's $18.00 altogether!"

Thus, two of the paradoxes of Britain. First, the pound sterling in the summer of '86 cost about $1.50, yet they spent just like dollars. In other words, our dollars were worth about 660 each.

British miles are the same size as American miles, only like the pound they seem to be 1.5 times as expensive. Britain's small scale seems to pack each mile with more, slowing you down and making 100 miles seem like 150. Daily mileage-about 125 miles-on the British Bat is quite conservative, so there's plenty of time to sleep late, see all you want and still get in a shower before dinner at 7:30.

At London we had come full circle. The first British Bat had been a rollicking success because of careful planning, good company, caring concern for our enjoyment and good health and an attitude on Rob Beach's part I can best describe this way: Whenever we asked him what the weather would be tomorrow, Beach would unhesitatingly reply, "Hot and dusty." No matter what the weather or situation, the sun was always shining in his soul-and that perhaps made him the battiest one of the bunch.

During our final days in London, we reluctantly handed back our BMWs, talked over our memories and cashed in our pounds. We then headed back to our familiar land where we drive on the correct side of the road, where people speak Amurrican and where we believe that things unseen are things not there.